The Strategy of Defeat

America has learned that the road to stabilizing the Palestinian territories, Iraq, Lebanon, Afghanistan and virtually the entire Middle East runs through Tehran. Unfortunately, it has not yet learned that a defensive military strategy cannot stop an aggressive enemy committed to conquest – unless that enemy believes that its very existence is at stake.

The asymmetry of waging a defensive war against an aggressive enemy surfaced during the Truman administration in its confrontation with Communist North Korea. When the Chinese Communists drove the UN forces out of North Korea in their quest to conquer the entire peninsula, Truman (to the surprise of the Chinese) failed to threaten the overthrow of the North Korean Communist regime adopting instead a defensive posture by choosing to wage the war in the South. As a result, American forces quickly became bogged down in a conflict with no clear end in sight. (1)

In 1961, the Kennedy Administration institutionalized this policy and morphed it into the doctrine of “flexible response.” The doctrine assumed that an enemy would more or less conduct war according to our rules of engagement and “get the message” if we gradually escalated the conflict in response to their aggression. While it may have worked on Khrushchev during the Cuban missile crisis of 1962, the doctrine proved to be useless against the Communist North Vietnamese who were committed to the conquest of South Vietnam and the unification of the country under Communist rule. Both Presidents Kennedy and Johnson adopted what amounted to a defensive posture in South Vietnam to counter the Communist threat from the North. As a result, five hundred thousand American troops were confined to South Vietnam with no thought of bringing down the Communist government of North Vietnam. Because of that strategy (according to a 1995 Wall Street Journal interview with Bui Tin, a former colonel on the General Staff of the North Vietnamese Army), North Vietnamese leaders felt confident enough even after their tremendous losses during the Tet Offensive to drag out the war until America’s will to fight was broken by the American anti-war movement.

This same failed strategy has dogged American military war strategy ever since. During the Iranian embassy crisis, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini told his Revolutionary Guards that they had nothing to fear from America after the Embassy take-over since President Carter’s only serious response to the hostage-taking was to impose ineffectual diplomatic and economic sanctions, an embargo on Iranian oil and a break in diplomatic relations – none of which threatened Khomeini’s regime. More aggressive U.S. action including capturing Iranian oil fields or conducting targeted bombings in Iran were ruled out as too dangerous. “Our youth should be confident that America cannot do a damn thing,” Khomeini told his followers three days after the embassy takeover. ”America is far too impotent to interfere in a military way here. If they could have interfered, they would have saved the Shah.” What especially surprised Khomeini was that Carter and his aides, notably Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, rather than condemning the seizure and the treatment of the hostages as a barbaric act appeared apologetic for unspecified mistakes supposedly committed by the United States and asked for forgiveness and magnanimity. In the end, Khomeini ordered the U.S. flag to be painted at the entrance of airports, railway stations, ministries, factories, schools, hotels and bazaars so the faithful could trample it under their feet every day – the ultimate insult. One could almost discern the words of Adolf Hitler after his 1938 meeting with British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain: “Our enemies are little worms,” Hitler told his General Staff. “I saw them at Munich.” America had lost more than its prestige in the eyes of Ayatollah Khomeini; it had lost its credibility.

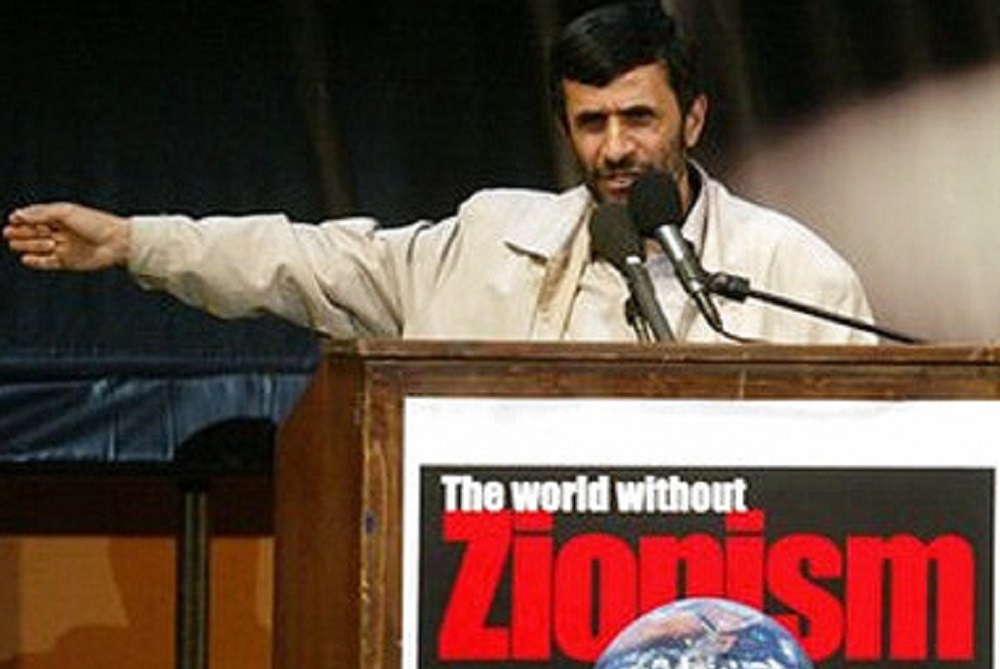

And President Clinton fared no better. His defensive approach to foreign aggression continued even as Americans were being harvested by Islamic terrorists from New York to Saudi Arabia to Kenya to the USS Cole in Aden Harbor. He sent cruise missiles to blow up empty tents in the Afghan desert and pharmaceutical factories in the Sudan, passed on “taking out” bin Laden, signed agreements with dictators based on the assumption that America would somehow be “safer”, hamstrung American intelligence services in the name of civil liberties, shrunk the American military in the name of economy, and chose to use the courts as the battleground, rather than engaging with the terrorists and taking the war to them and their sponsors. This led bin Laden to believe that he was dealing with an American “paper tiger” – a country that relied on rhetoric and dialogue, but never aggressive military action to secure its strategic interests abroad – the same mentality that has now led the Saudis, the Egyptians and Arab Emirates to mend fences with Iran’s Ahmedinejad whom they hate passionately, but whom they perceive to be the “strong horse” in the Middle East today.

If any of this sounds uncomfortably familiar, it should, because this same failed military strategy is now playing itself out in Iraq. Senior American officials report that approximately 75%-80% of foreign terrorists in Iraq are of Saudi, Libyan, Syrian, Algerian, Yemenite and Sudanese origin and have been provided with sophisticated weaponry and other logistical support by Iranian Revolutionary Guard units and an estimated 30,000 Iranian agents operating within Iraq. A Defense Department report released on December 19, 2007 emphasized that support for terrorist groups by Tehran’s Shiite government remains “a significant impediment to progress.” No kidding.

So the question arises: “How can America possibly stabilize, reconstruct or democratize Iraq, when Iran and its terrorist proxies are totally committed to humiliating us, breaking our spirit, destroying our efforts and ultimately driving us from the region?” During World War II, it would have been unthinkable for the Allies to have stopped at the German border and begun reconstruction efforts in liberated France in 1944 before destroying the Third Reich and de-Nazifying Germany. Similarly, the stabilization and reconstruction of Iraq can only be accomplished after we have brought down the mullahs and de-Islamified Iran. If the American people have grown weary of the war in Iraq, it is because the average American is tired of waging futile wars predicated on a failed military strategy. Americans want victory, not excuses and a military strategy based on a defensive posture can never defeat an enemy determined to wage a war of conquest.

Today, we hear rumblings of secret State Department negotiations with the Islamic Republic of Iran. What we fail to understand is that, in the Middle East, negotiations are simply a way to buy time. That’s Iran’s goal. For the U.S. to press for negotiations is seen as a sign of weakness, fear and defeatism. As such, negotiations with the mullahs at this late date will only serve to reinforce the power and influence of the Tehran regime and allow it to move on the fast track to uranium enrichment. Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and his President Mahmoud Ahmedinejad (and even our erstwhile Arab “friends”) believe that American resolve is faltering, that we have lost the will to retaliate, that we are divided, frightened and indecisive, and that’s why our flawed military strategy in the region is only facilitating the perception of American weakness. By removing the threat of military intervention and regime change, we have not only guaranteed a nuclear Iran, but our defeat in Iraq. The Iranians know it. The Arabs know it. And I suspect even the Israelis know it. We have sent a message to our friends and our enemies that we consider bringing down the mullahs and ending the Islamic revolution in Iran too costly to pursue even though we have exhausted all the alternatives. In so doing, we have conveyed the perception that although America possesses a vast technological advantage and great military power, it lacks the political will to use them against Iran.

As former Attorney-General John Ashcroft wrote in the final chapter of his recent book Never Again with reference to the events of 9/11: “I remember the cost of weakness. Misguided decisions always have consequences. In this war… a moral imperative for toughness exists. What will separate us from the mistakes of the past is our will to win” Like it or not, the responsibility for regime change and de-Islamifying Iran rests primarily with America and the many dissident Iranian groups seeking an end to the Islamic revolution and a return to stability, international acceptance and economic prosperity. If Iran is to go nuclear, we had best insure that a friendly government rules in Tehran. If not, no nation that ever opposes the mullahs’ global Islamic ambitions will be secure once their nuclear shield is in place.

ENDNOTES

When Eisenhower became President, he recognized that the North Koreans were committed to the conquest of the South. He therefore communicated to the North Koreans his intention to escalate the war by using nuclear weapons if they persisted in their aggression – and he meant it – and they knew it. Eisenhower was convinced that a defensive war was useless against an ideological adversary committed to the conquest of South Korea. From his perspective and based on his experiences in World War II, he understood that the challenge of the North Korean Communists had to be met just as America had met the challenge of an expansionist Nazi Germany bent on conquest. Eisenhower believed that the only response to total war was total war.